It’s the glamor-less topic that hardly anybody discusses but everybody has to do. For good hunts there are countless hours of windshield time behind it. It is the most important thing you could invest your time and money in to set yourself up for a successful waterfowl hunt.

It’s the glamor-less topic that hardly anybody discusses but everybody has to do. For good hunts there are countless hours of windshield time behind it. It is the most important thing you could invest your time and money in to set yourself up for a successful waterfowl hunt.

I was thinking about the article for a good hour before I actually put pen to paper, wondering how I could breakdown my method of scouting. The reason I find this hard to write, is because I learned all of it slowly, over spending days in the field, looking at topo maps on the web and eventually grew a knack for finding birds. It seems very simple and it is, but you just need to know what you’re looking for, and a general approach on how to do it. The question of the day? How do you find fields and sloughs to hunt ducks and geese?

The first piece of the scouting puzzle starts long before you put a foot to the accelerator. One of the best resources for a waterfowl guy is Google Earth, a free online mapping program. It gives you the ability to find fields, and water sources in stunning resolution from the comfort of your home. I’ll try to find areas with the most water as possible, surrounded by agricultural fields. A lot of land in South Dakota, and North Dakota are comprised of rangeland, not necessarily crops, and while I’ve hunted a lot of cattle ponds, birds don’t use rangeland to feed.

Here is an example of what rangeland looks like in comparison to agriculture, you’ll be looking for areas which look more like the second picture, which is labeled agricultural. You can see the row crops vs. the rolling look of cattle pastures.

Agricultural Fields

If we zoom in a little more, you can really see the difference, again you can see the cattle trails in the first picture, and the row crops in the second.

Now that you can see the difference in the different types of landscapes often found in prime waterfowl area, the next is how to pick out an area you want to target.

Often times a quick search of internet forums will provide you with towns a lot of people hunt. Do yourself a favor and mark them on Google Earth. Next, stay as far away as possible from them! Now this may be a little stretch, but I try to avoid popular areas. No doubt these are good areas but I don’t like to have to compete with 50 other hunters in an area.

When looking at the map, I’ll find areas at least an hour away from a major town So using North Dakota for example, try to stay away from the major populated areas such as Fargo, Grand Forks, Devils Lake, Jamestown and Bismarck. These are population centers, and popular areas for hunting and are often over flowing with people.

Now pick out areas with high densities of water. Finding big bodies of water with a lot of adjacent smaller potholes and lakes is a good bet. The large bodies of water will hold high concentrations of migrating ducks and the adjacent potholes will offer you realistic options for hunting water. Again, in these areas you will want to see agricultural fields mixed in.

I’ll pick 3 or 4 areas of around 20×20 miles to concentrate my scouting.

The next thing to do is jump car, however you are going to need a few things.

1. Cell Phone with Google Maps App

2. Good Pair of binoculars

3. Plat maps for chosen counties

4. GPS

5. Rubber boots

These things are all crucial so I can make the most out of my scouting trip. Waterfowl travel patterns are pretty simple. They will roost (sleep) on larger bodies of water, and right around sunrise they will head to an agricultural field. They will return to the roost or other ponds and lakes around 2-5 hours later, where they will spend the majority of their day. Again a few hours before sunset they will head to the field to feed.

Now this is the ideal schedule, but there are many things which can alter their patterns. For example, in the late season birds will often wait until 9 or 10 in the morning to get off the roost, head to a cut field and spend the rest of the day eating.

Now this is the ideal schedule, but there are many things which can alter their patterns. For example, in the late season birds will often wait until 9 or 10 in the morning to get off the roost, head to a cut field and spend the rest of the day eating.

The “ideal pattern” I described before is what we see 90% of the time and it’s what I base my scouting strategy from.

95% of the time I will scout an area the evening before I hunt it. I cannot stress how important this is! If you want to consistently shoot limits of birds, it’s something you NEED to do!

I’ll try to get into my scouting zone around 2 or 3 hours before sunset, and start driving around the bodies of water, looking for birds in the air. I’ll also be taking notice of what types of crops are in fields and if any of them are already cut.

When I talk about “cut fields”, it means agricultural fields which have already been harvested. When looking for birds to hunt in September, the majority of Geese and Ducks will be hitting wheat fields, as it’s often times the first ones cut. As we transition into mid-September, and farmers harvest Soybeans, this will be another quality food source for fowl. As October rolls around, the birds pretty much abandon wheat fields and use beans and corn as their primary food source.

When I talk about “cut fields”, it means agricultural fields which have already been harvested. When looking for birds to hunt in September, the majority of Geese and Ducks will be hitting wheat fields, as it’s often times the first ones cut. As we transition into mid-September, and farmers harvest Soybeans, this will be another quality food source for fowl. As October rolls around, the birds pretty much abandon wheat fields and use beans and corn as their primary food source.

However, corn is king! If there are birds in an area, and you find a cut corn field, more than likely there will be birds hitting it. Many times farmers cut their corn for silage, which is used for animal feed rather than for sale on the market. They will cut the corn all the way down to the ground, which is different than how they cut it for market. Either way, corn is king!

Back on topic! When I find a flock of birds, I’ll get on the accelerator and follow them until they find a destination to land. Often times even a single duck or goose can lead you to a mother load of birds.

It’s often helpful to have two people in the car, one driving and one keeping an eye on the flock. I’ve done it solo enough to multitask pretty well, but let’s just say it’s a miracle my truck never ended up in a flooded pond in the middle of North Dakota.

After I find the field, I’ll mark it on the GPS and continue to look for fields. The reason I don’t just sit there, is because I want to find at least one or two other back up fields in case something goes sour. After I’ve located two or three fields holding birds, I begin to analyze the fields.

If I am hunting geese in September, I’m looking for a field with over 150 geese in it, and ducks I’ll be looking for at least 200. After awhile, you become very good at estimating how many birds are in the field but initially I would count every bird in the field.

When we get into October, I look for honker fields of over 300 birds and duck fields of over 500. The number slowly goes up into November where I am looking for fields holding around or over 1k ducks and geese.

When I am analyzing a field I am looking for a few things. The first is, where EXACTLY the birds are sitting in the field. The next morning I want to be set up right where those birds were sitting the night previous.

When I am analyzing a field I am looking for a few things. The first is, where EXACTLY the birds are sitting in the field. The next morning I want to be set up right where those birds were sitting the night previous.

I’ll be looking for any topography in the field. For example if the weather man is calling for a north wind and the birds are sitting on a south facing slow, I know it’s not ideal and I’ll try to find a flatter area. As birds would rather not land going downhill.

I’ll try to set up on flat areas, the tops and bottoms of the fields, and so birds could land into a hillside, rather than trying to land going downhill. This is easy to find, as ducks and geese always land into the wind.

Stubble height is another important quality in which to rate a certain area in the field. You’ll want to look for areas with higher stubble which will allow you to conceal layout blinds more easily.

Looking at the structure of the flocks is also important as you want to make your decoy spread as realistic as possible. Are the birds spread out all over the field? Are they bunched up in a single area? If the birds are bunched up there is often something they are eating right in that area, there maybe a crop spill or wet area they are relating to.

In September birds will often be more spread out, sticking to family groups of 4-10 birds, while later and later in the season the more grouped up they will become.

The job isn’t done when you’ve collected all of this information, you can’t quite leave yet. The final piece to the puzzle is finding where these birds area roosting. That means following them back to water. Why does it matter you ask?

There is a lot of information you can glean from finding a roost. The first and foremost is figuring out which way they will be entering the field.

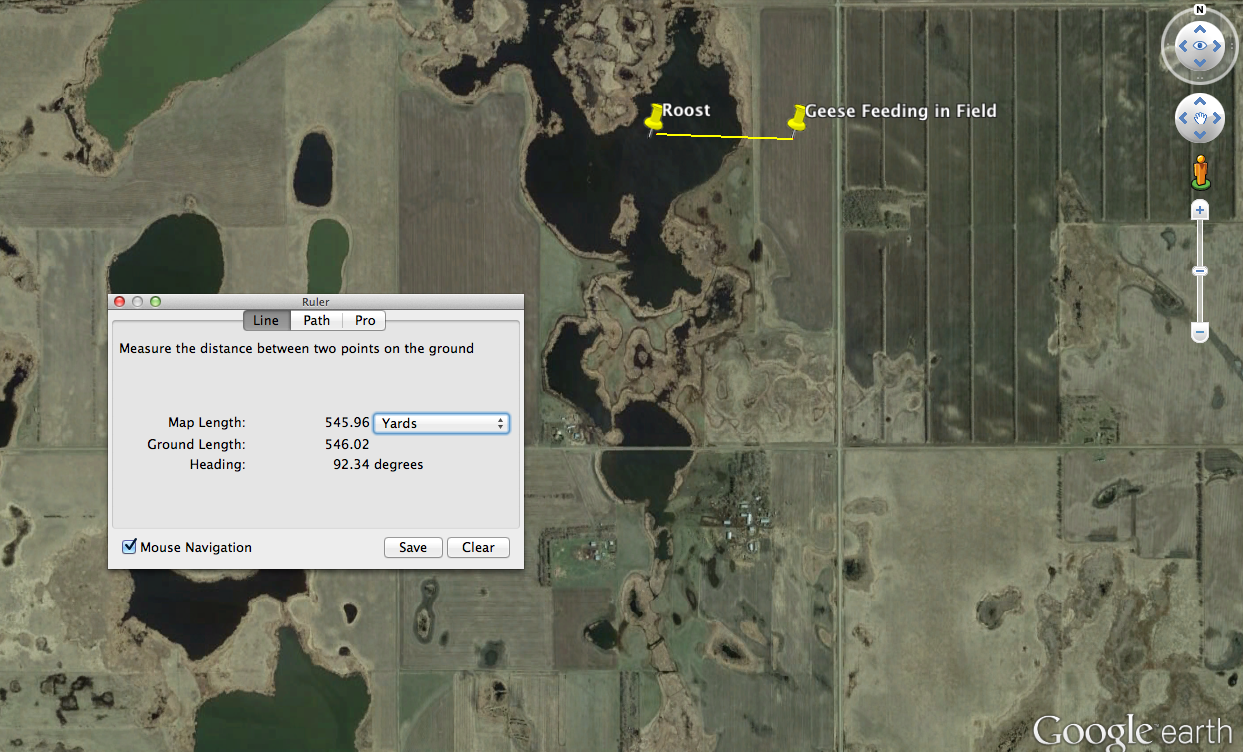

We will use this Google Earth Screen Shot as an example. There is a west wind which means the birds will be landing facing westward. They are using this wheat field and are feeding in the area listed, I’ve found they are roosting on the pond to the southwest.

That means the birds will have to come and swing around to the east before committing to the spread. This is crucial information, you will want to keep in mind for setting your spread in the morning.

Below is the same map with a different situation. There are 400 geese in the same field, and your are super jacked up about getting into an epic September goose shoot. You wait until nearly dark only to watch the birds jump off the field and head directly to the pond to the west of the field, only 200 yards from where they were feeding.

Time for plan B!

This is a prime situation, in where finding multiple back up fields will save your butt! You may be thinking Ben, if I find a field with 400 geese in September, I’m going to hunt it. All I have to say is good luck, you’ll just have to hope to shoot your entire limit in the first flock.

![]()

The roost is too close to the field, which happens quite often, especially in the early season. After you shoot at the first flock that comes off the roost, the rest of the birds are surely not going to come to your field after you massacred their comrades.

The roost is too close to the field, which happens quite often, especially in the early season. After you shoot at the first flock that comes off the roost, the rest of the birds are surely not going to come to your field after you massacred their comrades.

Putting distance between the roost and the field isn’t a bad thing. I’ve seen birds travel over 10 miles to hit a certain field, why they flew that far, nobody knows! As a general rule of thumb, you want those birds at least a mile away from where you are hunting.

After you’ve found where they roost, it’s the last piece of the scouting puzzle. Now there are all sorts of idiosyncrasies involved but these basic principles will get you in front of birds with the opportunity to mop them up!

Spot on. Went to school at UND for 4 years-lets just say my classes were scheduled around hunting season in the fall. Worst thing is getting to your field with someone else already in it, so i spent many nights sleeping in my truck. 2004-2008=best duck and goose hunting i have ever experienced. From Halloween to freeze up, this was the best time to find numbers of birds and even fewer less dedicated hunters….CORN IS KING.